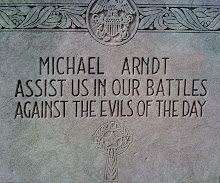

Posted by: Michael Arndt on January 11, 2010

Anyone who’s seen the documentary Food Inc. knows that Monsanto comes across as a thug. Its bioengineered soybeans, designed to be unaffected by Monsanto weedkiller Roundup, command 93% of the U.S. crop, yet there’s Monsanto in the 2008 movie, heartlessly hauling farmers into court to jack up its market share even further. Monsanto execs declined to comment then. In retrospect, CEO Hugh Grant now says he should have. He might have blunted the film’s impact if he had.

Grant has a different take on Monsanto’s role in agriculture, of course. From his point of view, the company is working on the side of angels, helping to create commodity crops to feed today’s population and the 2 billion more people who might occupy the planet by 2030. He is proud that Monsanto scientists were among the first to have a patented genetically modified plant on the market—Roundup Ready soybeans were introduced in 1996—and he is excited about new efforts to bioengineer wheat and vegetables, too, as well as the next generation of super beans and corn.

I got a chance to hear Grant’s perspective when he swung through Bloomberg’s office in Chicago the other day. (My colleagues at Bloomberg News posted this story on Monsanto’s patent strategy, and its legal fight with sometime partner/sometime rival DuPont.) Grant, 51, a big man with a Scottish accent and a shaved head, was joined by Robert Fraley, Monsanto’s chief technology officer, 56, a former Illinois farm boy who coincidentally wears the same haircut.

Monsanto’s goal within the next 20 years is to create plants that will produce twice today’s harvest. Fraley notes that when he went off to college in 1970, his family farm produced 75 bushels of corn from each acre. Today that average in the U.S. has more than doubled to 160 bushels an acre, and he predicts Monsanto scientists will come up with plants that will yield 300 bushels an acre. Moreover, farmers would use a third less nitrogen fertilizer than they add today.

“This isn’t a Jetson’s scenario,” Grant says.

Monsanto’s scientists employ two methods to devise more productive plants. One is traditional cross-breeding, though Monsanto has computerized much of the process so researchers don’t have to wait for crops to mature to know which combination will boost photosynthesis, say, or make a plant resistant to drought. A quick analysis of each plant’s DNA can tell them instead. The other method is bioengineering, or inserting new genes into a plant. They employ each technique roughly half the time.

One such genetic modification that excites Grant is a soybean that can produce Omega 3 fatty acids which are believed to reduce the risk of heart disease and have a number of other health benefits. For now, Omega 3 is found only in oily fish. This new and improved soybean also would be cleansed of trans fats and other saturated fats and become essentially as healthful as olive oil. Monsanto plans to have this patent-protected seed on the market in two years.

Further out: drought-resistant wheat and—cue the applause—winter tomatoes that taste like summer tomatoes.

Most of this research assumes, of course, that consumers and governments will OK more genetically modified organisms. Grant thinks that they will. Food scarcity has re-emerged as an issue, particularly in Asia and Africa. Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, India, and China have all opened the door to bioengineered crops or research in the 18 months, he notes. Even Europe might be becoming more accommodating, he adds. “Biotech isn’t a panacea,” he says. “But biotech has a role to play. We need more yields.”

This isn’t the story that appears in Food Inc., which is why Grant says he erred by not cooperating with the movie’s makers.

No comments:

Post a Comment