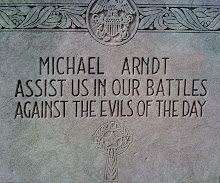

osted by: Michael Arndt on December 07, 2008

I’m participating as a fellow in a five-day program on innovation sponsored by the Salzburg Global Seminar in Austria. The title: New Models of Intellectual Property: Predictability and Openness as Spurs to Innovation. My classmates and instructors are from two dozen countries and every inhabited continent. The take-away after two days: There have got to be better ways to “incentivise innovation,” as Tim Hubbard of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute put it, than patents, which favor big companies with fattening monopolies.

(Stick with this: Hubbard comes back, and in video, too.)

One alternative: Collaboration, or open innovation. This notion isn't brand new, of course, especially in software. John Vaughn, executive vice-president of the Association of American Universities and its specialist in intellectual property, noted that a top exec from Procter & Gamble told the association in October that the company expects to get 50% of its new products from outsiders.

Another instructor, Douglas Graham, wants to create a social network on the Internet to help P&G and others find suitable--and trustworthy--partners. Graham, who left KPMG in 2000 after working (in vain) on knowledge-management systems, is executive director of Open Innovation Society. To join, members would all sign non-disclosure contracts. Then they'd be able to post research interests and seek out others who list the same ones. It's all theoretical, Graham told me. But he hopes to try a pilot program with the Canadian government in 2009.

But sharing secrets results in new problems. Gary Litman is the vice-president of the Europe and Eurasia Division at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Unlike many others, he doesn't applaud P&G's collaborative approach as an overdue break from the "not invented here" philosophy that has guided many leading corporations. Rather, he worries that P&G will end up reducing its spending on R&D the longer it goes down this course. That would diminish the company and could result in lots of itty-bitty advances and no blockbusters. His analogy: Detroit in the 1950s, when the only difference among cars was the garishness of their fins.

Hubbard sees another alternative. He believes in collaboration and collectives. But as he told me after his session, he'd also have governments or other deep-pocketed outfits establish competitions for inventions, and then pay the winner huge sums. How huge? Maybe $1 billion. Hubbard knows how competitions can hurry researchers on; at the Sanger Institute, he heads human genome analysis and was part of team that sequenced the third human genome in a race that was won the International Human Genome Project.

Contest winners for new drugs would still be awarded patents, under Hubbard's scheme. But to claim their prize money, first-place finishers would have to agree to turn over rights to generic drugmakers. They'd then pump out knockoffs such as new antibiotics--and at prices even the world's poor might afford.

I'll be back with more. In the meantime, here's a snippet of my interview with Hubbard:

No comments:

Post a Comment